Volkswagen, as a company, is unique as its very creation was a political initiative, rather than to fulfil the dreams and aspirations of an ambitious business person of a gifted engineer with a desire to carve out their niche in the car industry of the Twentieth century.

Founded only in 1936 by a political organisation known as the Deutsche Arbeitsfront (German Labour Front ) Volkswagen was the fruit of the tainted imagination of Adolf Hitler, who, as part of his vision of the one-thousand-year Reich, wanted to bring car ownership within reach of the “ working class.”

It remains a chilling fact that before Hitler and the Nazi party came to power, only one family in fifty could afford to buy and run a family car.

Most of the vehicles on German roads in the Twenties and Thirties were indeed large, luxurious and very expensive.

Most of the vehicles on German roads in the Twenties and Thirties were indeed large, luxurious and very expensive.

Hitler wanted to create a “Volkswagen” – which literarily translates to “ people's car” and was prepared to bring in the most talented people in the German automotive industry to make his vision a reality.

Before the developement of the Volkswagen, a number of German car makers who produced compact cars, with probably the most successful being Hanomag with their rear-engine "Komissbrot". The Komisbrot enjoyed particular popularity during the mid to late Twenties before being discontinued, perhaps due to lack of profitability.

Before the developement of the Volkswagen, a number of German car makers who produced compact cars, with probably the most successful being Hanomag with their rear-engine "Komissbrot". The Komisbrot enjoyed particular popularity during the mid to late Twenties before being discontinued, perhaps due to lack of profitability.

The Nazi Party attached great importance tolaunching the Volkswagen and, were less concerned about issues of profit and loss. They were prepared to invest, and on a large scale, to get the project moving.

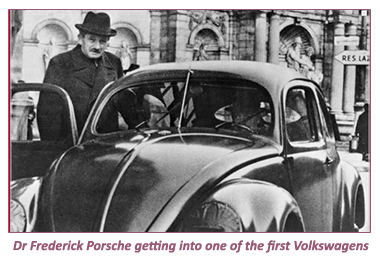

The first step was an approach to Dr, Ferdinand Porsche, one of Germany’s top auto designers, who, as an independent, had worked for most of the country’s top companies.

Dr.Porsche had been known to be interested in designing a compact family car but had found no takers among his usual clients.

Dr.Porsche had been known to be interested in designing a compact family car but had found no takers among his usual clients.

In fact, during the early Thirties, Porsche had created a working prototype of an air-cooled rear engine “ Volkswagen, whose exterior design was based on a "beetle" shape.

Porsche was confident that this unusual shape would reduce the cost of running the car considerably thanks to dramatically improved aerodynamics.

According to various reports, Hitler even visited Dr, Porsche in his studio in Stuttgart during 1934 to view the prototype, and was impressed enough to give his approval to put the “ people’s car” into production.

The next significant logistics problem that Porsche had to overcome was how to produce the Volkswagen in the massive bulk that it would require fulfilling Hitler’s vision to provide an inexpensive yet robust family car for the millions who would enjoy it.

Dr Porsche soon arrived at the conclusion that none of the existing German car plants had the desire or ability to produce a Volkswagen.

The only way was to establish a facility that would be custom designed just to build this particular model.

With the Third Reich giving their full approval and unlimited financial backing Porsche and his team began to examine possible locations for the new plant. They eventually decided on a small town, Fallersleben adjacent to the city of Wolfsburg, in the Lower Saxony region of Northern Germany.

By the time production was ready to begin, Porsche and his team were well aware that the Volkswagen project could never be financially viable. It appears that neither Dr Porsche or any of his management team were prepared to bring that piece of news to Hitler, so the project went ahead.

By the time production was ready to begin, Porsche and his team were well aware that the Volkswagen project could never be financially viable. It appears that neither Dr Porsche or any of his management team were prepared to bring that piece of news to Hitler, so the project went ahead.

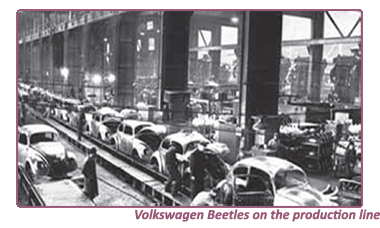

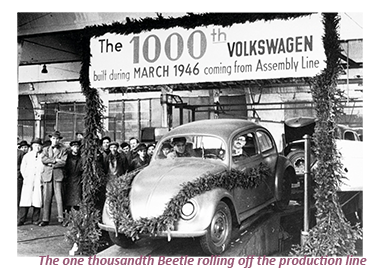

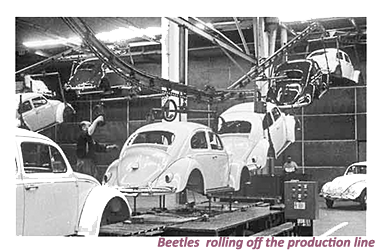

Many thousands of these so-called “ prototypes” were believed to have been produced in the late Thirties and early- Forties.

Just when the Wolfsburg plant was about ready to begin marketing the Beetle to the German public, Germany’s increasing involvement in World War Two meant that the plant’s facilities had to be turned over for the war effort.

Volkswagen’s particular speciality was a strange looking utility vehicle known as the Kübelwagen, while some of the production was set aside to produce an amphibious vehicle, known as Schwimmwagens.

During the war, as the Allied forces became aware that Volkswagen was involved in production for the Nazis, air attacks on the Wolfsburg plant grew in intensity.

When the armistice agreement was signed in 1945, Germany, or West Germany, was in ruins, Hitler, by that time entirely disillusioned with the Volkswagen and trying to conquer the World, had committed suicide in his bunker in Berlin.

When the armistice agreement was signed in 1945, Germany, or West Germany, was in ruins, Hitler, by that time entirely disillusioned with the Volkswagen and trying to conquer the World, had committed suicide in his bunker in Berlin.

Dr Frederick Porsche rapidly washed his hands with Volkswagen and went off to produce his own cars in Stuttgart and wanted nothing more to do with the Beetle.

The West German population was defeated, millions had lost their lives, and those who survived were penniless and in ooor health.

The chances of putting the Volkswagen plant back into operation at that point appeared to be incredibly slim.

That was until Major Ivan Hirst of the British Army appeared on the scene.

As fate would have it, it was Hirst, who was handed the responsibility of running the Wolfsburg plant after it was captured by Allied forces just a few weeks before the end of the war.

![]()

Many people would have made the minimum of effort to save the plant, instead rapidly selling off any usable pieces of production equipment as well as raw materials for the highest price to pay for war repatriations.

Many people would have made the minimum of effort to save the plant, instead rapidly selling off any usable pieces of production equipment as well as raw materials for the highest price to pay for war repatriations.

Hurst, a no-nonsense engineer from the city of Oldham in North-Western England, saw the potential in the plant, but ironically not in the Beetle.

Instead Hurst saw a future for the Kübelwagen, which he thought could have some use for occupation troops in the coming years.

Anxious to help the local population, who were badly in need of income to feed themselves and their families, Hurst convinced the Allied administration to order 20,000 Kübelwagens which would have guaranteed the future of the plant for a number of years.

Anxious to help the local population, who were badly in need of income to feed themselves and their families, Hurst convinced the Allied administration to order 20,000 Kübelwagens which would have guaranteed the future of the plant for a number of years.

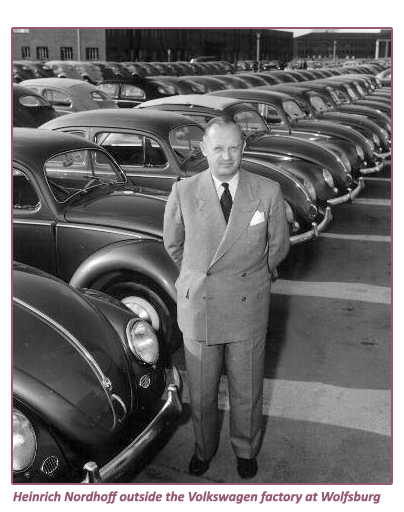

With little knowledge of German and even less of the lie of the land in and around Wolfsburg, Major Hirst once again displayed his considerable common sense by employing Heinrich Nordhoff to be the production manager for the plant.

Nordhoff, then in his mid-Forties, had a wealth of experience in the car industry in Germany, working for BMW before the war and in the immediate post-war years as an advisor for the occupation forces.

The unlikely combination of Hirst and Nordhoff proved to be a highly productive one, with the pair working together to solve the day to day problems of the plant, in particular, the chronic shortage of raw materials and the generally low level of morale and health of the production staff.

![]()

Despite these difficulties, the Volkswagen factory, as it was now known, looked like it could be a viable business, mainly as demand for the Beetle was steadily on the rise.

Eventually, to Hirst and Nordhoff’s credit, the decision was made to sell Volkswagen as a going concern.

Feelers were sent out to the significant influences in the car industry, especially those based in the United States, but no serious buyers were found.

With Ivan Hirst due to return to the UK in 1949, once again the future of Volkswagen was looking doubtful.

At the very last minute, the West German government, in conjunction with the administration of the State of Lower Saxony, stepped in to save the company, investing the minimum of capital to do so.

At the very last minute, the West German government, in conjunction with the administration of the State of Lower Saxony, stepped in to save the company, investing the minimum of capital to do so.

This situation was far from ideal leaving Volkswagen to rebuild itself under Heinrich Nordhoff’s guidance.

All things being equal, Nordhoff did an excellent job in keeping Volkswagen afloat although he did become the subject of increasing criticism for his reluctance in expanding the range of vehicles produced at Wolfsburg.

During his tenure, Nordhoff was responsible for the release of just two vehicles to the Volkswagen range, one of them the iconic Type 2 van ( also available as a pickup and camper), and the other the Karman Ghia sports car, which even went on to become an icon in its own right.

During his tenure, Nordhoff was responsible for the release of just two vehicles to the Volkswagen range, one of them the iconic Type 2 van ( also available as a pickup and camper), and the other the Karman Ghia sports car, which even went on to become an icon in its own right.

While the “Bug” as it was generally known had tremendous appeal and sold in unprecedented quantities, by the Sixties, despite innumerable cosmetic facelifts, the design was outdated, although it defied all logic by continuing to be a high seller across the globe.

By 1973, when production was restricted to South America and Africa, total production had reached to over 16 million in a production span that reached close to forty years.